The term “personality disorder” can cover a range of diagnoses.

Mind separates these into three categories: Suspicious (Paranoid, Schizoid, Schizotypal); Emotional and Impulsive (Anti-Social, Borderline, Histrionic, Narcissistic); & Anxious (Avoidant, Dependent, Obsessive Compulsive). For more information on the specifics of each of these, we recommend this article

The way personality disorders are classified by professionals is changing.

In the UK, the NHS uses what is called the “International Classification of Diseases” (ICD) as its ‘textbook’ base for diagnosing and treating physical and mental disorders, which is created by the World Health Organization. There is also the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM) which is probably more widely heard of, but this is actually the guide book used by the USA, and not the UK. It’s important to note that the names of these manuals (with words such as “diseases” and “mental disorders”) do not reflect the way mental health problems are approached by most medical professionals in practice!

The DSM classifies personality disorders into three categories (cluster A, cluster B and cluster C), similar to the one referenced by Mind above. However, as of January 2022, the ICD is releasing a new way of categorising personality disorders which separates them by the intensity of the symptoms – mild, moderate, severe – and has what is called “trait domain qualifiers” which are similar to the subtypes used by the DSM.

There is a lot of understandable criticism about this new way of classifying personality disorders, and for more about this, the podcast episode “The Upcoming Changes to “Personality Disorders” with Mike Crawford” by the Wrong Kind of Mad Podcast is very good.

The trait domain qualifiers can be a good way of explaining how a personality disorder might feel and the kind of symptoms expressed. They are as follows:

Negative affectivity

Experiencing a broad range of negative thoughts and feelings — including anxiety, shame, anger and low self-esteem — with a frequency and intensity that might be experienced by others as out of proportion to the situation.

Detachment

A tendency to maintain both social and emotional distance from people, which might look like avoiding social interactions or close friendships.

Dissociality

A disregard for the rights and feeling of others, often meaning someone acts in a self-centred way and seems to lack empathy.

Disinhibition

Acting impulsively or rashly based on sensations, emotions, or thoughts, without giving proper consideration of the negative consequence which could arise as a result of behaviour.

Anankastia

A narrow focus on perfectionism and ideas of rights and wrong, which can often lead to controlling both one’s own behaviour and the behaviour of others.

These trait domains don’t necessarily apply to everyone with a personality disorder and are intended to present different ‘sub-types’ similar to what the DSM and Mind use.

They can also feel hurtful to read if they do apply. This is when it’s important to remember that, whilst the causes of personality disorders are not fully understood and still being researched, it’s believed to be because of both genetic factors and challenging life experiences. In short, people with personality disorders have usually faced really difficult and traumatic times in their life, and this can manifest in behaviours that are completely understandable ways of coping with the pain and distress. For example, if someone has experienced abuse from people close to them, it’s understandable that they might then show signs of detachment to try to protect themselves from getting hurt again.

It’s really important to say that recovery – however you might choose to measure this – is achievable. And as the difficulties experienced by someone with a personality disorder are complex and frequently connected to overwhelming feeling states, the effective treatments are psychological services (talking therapies).

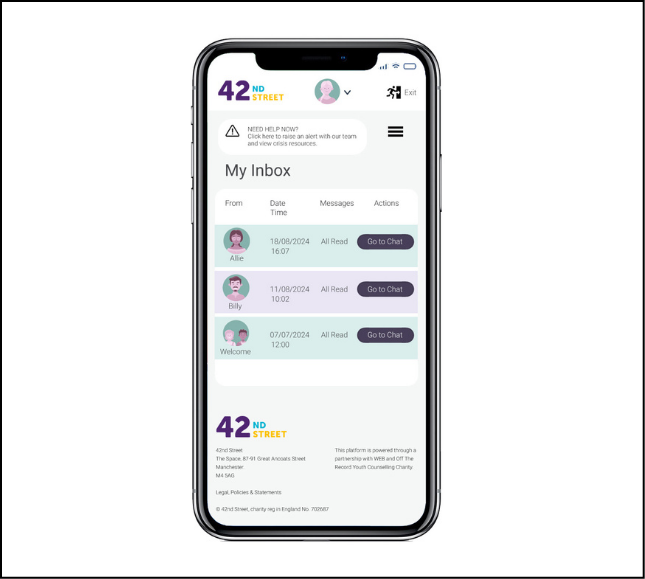

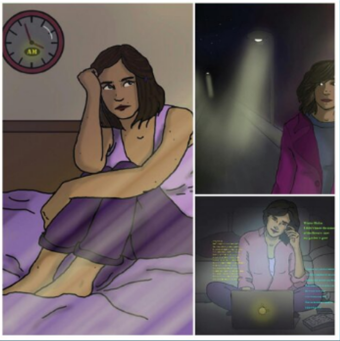

The best way to understand how it might feel to have a personality disorder is to hear directly from people who have experienced them – something which is often overlooked. Along with 42nd Street, current and ex-service users, as well as staff members, who have experienced (either directly or through their work) one particular kind of personality disorder (Borderline) made these videos about their experiences.

Issues with the term “personality disorders”

It’s too broad

One of the criticisms of the diagnosis is that it covers such a range of difficulties people encounter that trying to offer a definition which covers all of them means you end up with something vague and consequently unhelpful. Someone with one type of personality disorder may present completely differently to someone else with a different type – or even someone with the same type. There are queries about if it is helpful to group such a range of experiences and difficulties under one label.

Disagreement between specialists

There is a lot of disagreement among professionals about understanding personality disorders, which can you read more about here.

Insensitive wording

Another obvious criticism is the wording of “personality disorder”. People’s personalities are so key to who they are, that to label someone’s personality as “disordered” can feel hurtful and damning. This unhelpful use of the word “personality” also stands at odds with the fact that recovery from a personality disorder is possible. Everyone’s personality is multi-faceted and contains ‘good’ and ‘bad’ elements, and the label of personality disorder can make it sound like someone’s whole personality is ‘bad’, which just doesn’t reflect the nuances of all the different things which make up a person.

A lot of people have reported experiencing stigma when presenting to medical professionals with a personality disorder diagnosis. This can lead to people feeling that they receive less or no care from services.

Again, these videos made by people who have experienced personality disorders expand more on this.

Where to go for more support

- Speak to your GP if you feel able to. This can hopefully help to make sense of what you are going to and could lead to more support from specialist services.

- Seek support from 42nd Street. While we can’t diagnose or offer specialist one to one support for personality disorders, our services will give you a space to talk about your feelings, help you to understand your behaviours and develop positive coping strategies when difficult feelings come up.

- If you’re over 18 we also run a Therapeutic Community group that you may find helpful too. You can read about how that works here. Overall, though, every service provides you with someone who will listen, acknowledge your feelings, and work with you to develop ways to manage your emotions. You can read about our services here.

- Mind has a lot of information on personality disorders, including the different types, potential causes, treatment options, and advice for family and friends.

- Rethink Mental Illness goes into a lot of detail about personality disorders, different types of therapy and more. They’ve also compressed all of this information into a downloadable factsheet, which may come in useful both for yourself and those around you.

- Mad Covid is an intersectional mental health community for survivors and service-user led projects. They run various projects and write about mental health issues. They also do a podcast, which has focussed on ‘BPD/EUPD’ for one of its episodes, which you can listen to here.

- Recovery in the Bin are a group of mental health survivors and supporters who write interestingly and critically about personality disorders and mental health generally.

Other Articles you may be interested in