This article mentions homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, racism, sexual violence

long read 12-15 mins

Exploring queer women’s shared history, identity, and ownership of language

As young queer women and girls, it can sometimes be tricky for us to navigate our way through the debates and discussions in our community, especially on social media. A lot of these discussions tend to revolve around the usage and ownership of language – questions such as ‘who can claim this identity?’ and ‘who can use this word?’ when it comes to terms like butch and femme, with many of the conclusions leaving some of us feeling overlooked and outcasted.

From this, I raise another question that I want to explore together in this article: how can we embrace our own unique identities and communities, whilst also celebrating our sisterhood and keeping solidarity at the heart of our conversations?

So where to begin?

As queer women, we’re naturally linked by our shared history. The origins of the terms a lot of us use now to understand our identities have bloomed from the same seed - the term ‘lesbian’ came after ‘tribade’ fell out of use, and began as a way to refer to sexual acts rather than any identity or label a person took on. The term ‘bisexual’ had similar origins, when in 1892 it was created and used in a completely medical sense up until the 1970s. We only really began to reclaim ‘lesbian’ from its medical context in the 1920s, and the meaning didn’t make any distinction between who was exclusively attracted to women, and who wasn’t. This means that in almost all historical contexts and uses of the term ‘lesbian’, it refers to all queer women.

“But usually what writers comment on [in the 17th and 18th Centuries] is the quality of passion between two women, not their personal histories. Lesbian culture seems to have been understood as a matter of relationships and habitual practices rather than self-identifications. Whether or not a woman also had loving relationships with men, her passionate connections with women were worthy of comment.”

Emma Donoghue, Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668–1801 (1993)

But what about the other labels that queer women use to identify as?

Two of the most well-known identity labels for queer women are ‘butch’ and ‘femme’. The coining of the term ‘femme’ in relation to queer women’s identity is often accredited to Anne Lister, an English diarist in the 19th Century who was dubbed ‘the first modern lesbian’. In her diaries, she said about her partner ‘Plus femme que moi’ which translates to ‘She is more womanly than me’. However, Lister’s partner Marianna also had romantic relationships with men, meaning that even since the first usage of femme as a descriptor, bisexual and pansexual women have been very much a part of that, despite modern discussions tending to erase this.

In the 1920s, even more terms came about and grew in popularity through the rise of ball culture in America. Within ball culture, houses serve as ‘found families’ for queer youth (who are most often Black and Latine) who aren’t safe in their original homes because they are LGBTQIA+. The labels ‘butch’ and ‘femme’ were used in these spaces to embody the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality, as shown in the TV show ‘Pose’.

Around the same time in the US, a culture formed among working-class queer women in urban communities, and the crossovers with ball culture led to butch and femme being used in these spaces. Lesbian bars were set up and began to thrive in the 1940s. Looking back now at the sources and literature of the times, it gives the impression that only “lesbians” (i.e. women exclusively attracted to women) frequented these bars, however at the time ‘lesbian’ still encompassed all queer women - in these spaces, people who might now have identified as lesbian, bisexual, or pansexual all played an equal role in creating and taking part in the culture.

“In lesbian writing the term femme, which came into common usage in the 20th Century, most often refers to a feminine dressing and acting lesbian or bisexual woman. […] During the mid-20th century, a working-class bar culture in Europe and America made femme roles visible to the world.” (p. 64)

Meredith Miller, Historical Dictionary of Lesbian Literature (2006)

This rise of lesbian bars in the 40s led to LGBTQIA+ people feeling safer in expressing their identities, especially those from the working-class. Butch and femme presentation became even more important as it served as a way for queer women to identify each other and defend themselves during police raids of bars and other queer spaces.

Returning to the unavoidable question... who can say they’re butch or femme?

Nowadays, most people are likely to associate the terms butch and femme with the lesbian community, and some non-lesbians also agree that these terms shouldn’t be used by those who don’t identify specifically as lesbian. ‘Stag’, ‘tomcat’, and ‘doe’ have since been created as alternatives for bisexual people to use, but many still don’t feel comfortable with these terms, or with being excluded from using the original terms they helped create and form the history of. Most of all, many bisexual people of colour reject using these labels because of the associations with hypersexual animals, alongside the vast history of black people having similar racist comparisons made against them.

As a lesbian, when I consider that the labels of butch and femme as we know them today originated within ball culture among LGBTQ+ people of all identities, it feels as though the opinion that only lesbians can use these terms - whilst often coming from well-meaning people - tends to miss a lot of the history and context. If we exclude other queer women from these terms, it erases our shared history as a group that has, for a majority of that history, all identified and coexisted peacefully under one label. To exclude queer and trans people of colour erases the safety these terms give them in their identity during times of persecution, and ignores their significant contribution to the creation and popularisation of butch and femme as identity labels.

So where exactly does this view that only lesbians can use these terms come from?

In the 1970s, a culture war came about in the form of the separatism movement. It was led by the Furies Collective, a group of twelve white cisgender women, with Sheila Jeffreys at the forefront. In an early pamphlet Jeffreys made promoting radical feminism, she defined the political lesbian as ‘a woman-identified woman who does not [want to be intimate with] men’, and claimed that straight and MGA (multiple gender-attracted) women were ‘collaborating with the enemy’. Her argument was that all feminists should choose to become ‘lesbians’, but that attraction to women was not necessary to be a political lesbian; the majority of the women involved in this movement were heterosexual.

There was a rapid rise in popularity of the separatism movement, and the view that any form of masculinity harms women - this quickly began to cause huge shifts among the community of queer women. Butch women were seen as trying too hard to be like men, whilst femme women were framed as only having relations with women in order to appeal to men. Butches and femmes in relationships with one another were criticised for upholding heteronormativity. As a result, they were side-lined, and androgyny became the new more ‘progressive’ way for lesbian feminists to present themselves.

“In the 1970s, however, as lesbian feminists sharpened the boundaries around lesbian identity and the lesbian community, the once amorphous “ghost” of female bisexuality solidified.”

Lauren Jae Gutterman, Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire Within Marriage (2019)

With events like the Stonewall riots in 1969, and a general rise in homophobic hate crimes in the following decade, heterosexuality was seen as something to be feared. The result was that MGA women, who were seen as being ‘closer’ to heterosexuality, were slowly pushed out of spaces that were originally made to include them. Separate bisexual groups began to form, as many felt unwelcome among lesbians and gay men. In 1988, the acronym LGB officially distinguished between lesbian and bisexual, and lesbian became commonly accepted to mean being exclusively attracted to women.

“It remains common to hear lesbian feminists argue that bisexual women dilute the movement. Bisexual women, however, have been in the lesbian feminist movement all along — perhaps the movement has always been diluted. It seems to me that bisexual women do not dilute the movement; rather, there are lesbian feminists who would weaken the movement by kicking them out.”

Sharon Dale Stone, Bisexual Women and the “Threat” to Lesbian Space: Or What If All the Lesbians Leave? (1996)

From this point forward, MGA women started being excluded from their own history - ‘lesbian’ now meant exclusively women-attracted, but almost all of queer women’s history prior to the 1960s used the term lesbian. ‘Butch’ and ‘femme’ were seen through the lens of the modern definition of lesbian, and MGA women were denied these identities that they had helped form. Although commonly called the ‘separationist movement’, looking back it seems to me that the more likely reality was that MGA women were being driven out of a community they had always previously been an innate part of, and a resulting split began to form in our solidarity with one another.

“In an essay called ‘Who Hid Lesbian History?’, Lillian Faderman has exposed hostile biographers’ strategies of ‘bowdlerization, avoidance of the obvious, and cherchez l’homme’ (look for the man). But who hid bisexual history? Lesbian historians must take some of the blame; redressing the wrongs done by lesbian-hating biographers, they have often edited the lives of women who loved both sexes into exclusively lesbian histories.”

Emma Donoghue, Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668–1801 (1993)

Where does this leave us now?

In my view as a femme lesbian, I understand how some butch and femme lesbians may feel protective of their labels, due to the history of radical feminists watering down the meaning of butch and femme culture and the importance of this active choice of presentation for lesbians. Even still, I think it’s important for us to acknowledge how the gatekeeping of lesbian history, identity, and spaces, functions through driving a wedge between us and our MGA sisters, as well as trans women (as this mindset wrongly assumes they benefit from male privilege) and queer women of colour (who share oppression with men, so can’t exclude men from their politics).

Things are slowly improving: research by IU's Center for Sexual Health Promotion, which compared attitudes towards bisexual people from 2013 and 2016, concluded that attitudes had improved from being negative to overall more neutral. However, bisexual women are still significantly more likely to be victims of sexual violence (61%) than lesbians (43%) and heterosexual women (35%), and bisexual people in general face ‘double discrimination’ from heterosexual people, as well as gay and lesbian communities, leading to negative impacts on mental health.

This shows we still have a long road ahead of us in terms of mending the cracks in the sisterhood of queer women. Nonetheless, I have faith that approaching difficult conversations around identity and language ownership with compassion, understanding, and solidarity will help bridge the gap and support those who feel excluded or left behind. Through raising more awareness of our shared history - especially among young queer women and girls - and by reflecting on the reality of our communities today, we can work towards coexisting with greater harmony whilst also embracing our own separate communities and the comfort these spaces bring us.

Where to go for more support

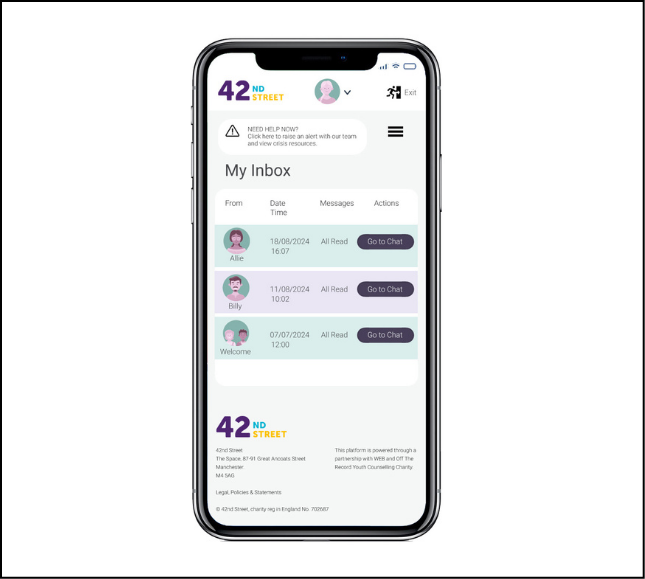

The journey to understanding your identity can be pretty tough at times, especially when the confusing discourse among groups in the LGBTQIA+ community is added into the mix. If you’re between the ages of 13-18 and are interested in exploring the topics mentioned in this post a little more, 42nd Street’s very own Q42 project can be a great safe place to do that. Mind also has a great, accessible list of resources to help support LGBTQIA+ young people across the UK.

If you feel you need further support and you want to chat to someone online via messages, you can register for ongoing online support via our online support portal. We also hold weekly drop-in sessions so that you can speak with a worker without an appointment.

We provide a number of face-to-face services too, all of which offer something slightly different depending on what’s best for you. Overall, though, every service provides you with someone who will listen, acknowledge your feelings, and work with you to help find resolutions. You can read about our services here.